July 27, 2014

|

On the postdocalypse

I've been following several blogs from scientists around the world (my favourites being in the pipeline, RRResearch, mindthegap and NoComment). Another blogger that I've discovered some time ago is Ethan Perlstein, a Harvard trained PhD who got a prestigious postdoc grant to join Princeton and run his own lab. Browsing through the web on a very hot sunday afternoon I was shocked and surprised to discover that he abandoned his plans for staying in academia and founded his own life-tech startup in the bay area. A good article in Mother Jones on the rather aptly named "Postdocalypse" nicely sums up his motifs and the reasoning behind this step.

Scenes from the Postdocalypse

How do you become a scientist? Ask anyone in the profession and you'll probably hear some version of the following: get a bachelor's of science degree, work in a lab, get into a Ph.D. program, publish some papers, get a good postdoctoral position, publish some more papers, and then apply for a tenure-track job at a large university. It's a long road—and you get to spend those 10 to 15 years as a poor graduate student or underpaid postdoc, while you watch your peers launch careers, start families, and contribute to their 401(k) plans.

And then comes the academic job market.

. . .

Ethan Perlstein was one of these postdocs—before he decided he'd had enough.

. . .

"when I encountered what I have been calling the postdocalypse, which is this pretty bad job market for professionally trained Ph.Ds—life scientists, in particular." After two years of searching for an assistant professorship, going up against an army of highly qualified, job-hungry scientists, he gave up.

Source: Indre Viskontas and Chris Mooney at Mother Jones

|

Ethan has in my view all the hallmarks of a great scientist: innovative research, excellent publication record, good communication skills (his brilliant website and blog), and a knack for alternative and unusual funding sources (crowdfunding).

The question really is if he thinks its impossible, then who can make it these days in academia and how do they make it?

I've been discussing this question a lot with postdocs here in the Division and the mood has turned very sour and desperate in the last 3-4 years. Postdocs stay now a lot longer in the lab than ever before. And it takes much more to transition away into your first faculty position, if you choose to stay in academia (which is what you have essentially been trained for during your time as a postdoc).

Among other things this led to the emergence of positions like "Assistant Project Scientists" (or "postdoc plus" as I call it) at universities that allow employment for only 5 (in exceptions 6) years as a postdoctoral scholar.

If you don't find a faculty position during that time, you either recycle yourself in yet another postdoc position, transition into industry, change career paths or simply give up. However, even if you leave academia, the job prospects are rather dim at the moment, see this recent article in Slate.

To their credit, the (at times rather slow) NIH has finally recognised the 'disaster' that is happening right now.

Despite the paucity of the data on the current state of postdoctoral researchers, it is evident that the postdoctoral period has become a holding pattern for many young researchers. Although a postdoctoral fellow is considered a trainee, in many laboratories fellows receive little additional preparation for their future careers, even for those in academic research. For example few postdoctoral fellows receive instruction in grant writing, laboratory and personnel management, and teaching, all skills that are necessary for a successful academic career.

. . .

This system leaves trainees in subordinate positions at a time when they are expected to be highly productive as independent investigators.

Source: NIH Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group Report

|

However, despite their recognition of the problem I am not convinced by their solutions: more training grants for younger scientists, partner with industry, increase salary and benefits, double the number of K99's with shorter eligibility period.

Particularly the shorter eligibility period for their K99 grants (which are a MAJOR chance to make the transition into a faculty position) will be tough on postdocs working on projects that TAKE TIME. Specifically postdocs that work on a project involving the generation and thorough analysis of a (knockout) mouse model will have a very hard time. From personal experience I know that you need at least 2-3 years to get a decent manuscript out (if you are lucky). However you need publications for that impressive CV that gets you the K99. . .

The current job-prospects for postdocs (and junior faculty) in life-science are also nicely shown in this infographic from Jessica Polka at the ASCB.

The data show that landing a tenure-track faculty position clearly is an "alternative career" path, that only a minority of postdocs will achieve. So what 'lands you the job of your dreams in academia these days'? Here are several key factors (in my view):

- luck

- your network (collaborators, an established mentor in the field)

- your publications (quantity, quality, CNS almost a must)

- a grant (e.g.:K99) or some other source of funding that allows you to transition from postdoc to faculty

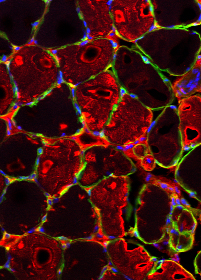

- you work in the one of the 'hype' fields - at the moment these are in my view neuro-something, stem cells/regeneration, epigenetics, big data (-omics) coupled with an en-vogue technique (e.g. mass-spec)

- your CV (better be from a big name university with loads of awards and such)

- particularly if you plan to be in a "school of medicine" even if you 'just' do research it helps to have an MD

- tenacity and the resources to 'stick to it'

- a good research idea/project

So what happens when you land that 'dream' job? While it is almost impossible to get that position these days, keeping it under the current federal/state funding climate is near hopeless without the backing of your university, luck in grant writing, or some 'alternate' funding sources (industry, donors, foundations). And things are looking somewhat bleaker when you are in the unlucky position to be have the "Adjunct" in front of your title (like I do). You realize very quickly that your options are somewhat more limited.

Just to give an example: I was somewhat distraught and disappointed to discover that several alternative funding sources like the Pew Scholars Program or the Searle Scholars Program only allow ladder rank junior faculty to apply (aka - the ones that have hard money from the university and are essentially tenured). You can have the best and most innovative science, but if the prefix to your title happens to be the wrong one - well, bad luck.

So what now? Abandon all hope? Give up?

For me (and my research) it will be crunch time very soon. I have to apply for a big NIH grant (called R01) very soon. If I am unable to secure this funding source, then I have to close up shop at UCSD, as I have no other resources. And I have only time for 2-3 attempts left with a rather low chance before my funding runs out. . .

Bleak outlook indeed.

As for Ethan Perlstein - judging by the website of his lab/startup it looks like 'life is great' in the little niche that he carved out for himself. Pretty impressive. I would not be surprised to see him on the cover of Forbes as a multimillionaire in a couple of years (after he sells his lab/startup to big-pharma), saying that making this change from academia to industry was the best decision he ever made. Good luck!

|